Six Sigma. Amazingly, Ramanujan was able to provide a number of interesting identities for this function. I wonder if he knew that this is what some of his functions looked like. Ref. Hardy & Wright.

Imagine Six Sigma.

Phase Two.

Gee Two. The modulus of the Weierstrass ellipic function invariant g2 as a function of the square of the nome q=exp (i pi tau). The zeros of this function are the blue dots. These get faint as they approach the edge of the disk; a clearer view of the zero can be gotten from the phase diagram, several images below.

Really Gee Two. The real part of the Weierstrass ellipic function invariant g2 as a function of the square of the nome q=exp (i pi tau). The real part is negative in the black areas, and positive in the colored areas. Blue denotes smaller values, passing through red for the larger values.

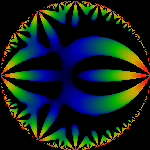

Imagine Gee Two. The imaginary part of the Weierstrass ellipic function invariant g2 as a function of the square of the nome q=exp (i pi tau). The imaginary part is negative in the black areas, and positive in the colored areas. Blue denotes smaller values, passing through red for the larger values.

Really Gee Three. The real part of the Weierstrass ellipic function invariant g3 as a function of the square of the nome q=exp (i pi tau). The real part is negative in the black areas, and positive in the colored areas. Blue denotes smaller values, passing through red for the larger values.

Imagine Gee Three. The imaginary part of the Weierstrass ellipic function invariant g3 as a function of the square of the nome q=exp (i pi tau). The imaginary part is negative in the black areas, and positive in the colored areas. Blue denotes smaller values, passing through red for the larger values.

Phase Gee Two. The phase of the Weierstrass ellipic function invariant g2 as a function of the square of the nome q=exp (i pi tau). The phase runs from -pi in the black areas, 0 in the green areas, and yellow-read in 0 to +pi regions. Note that the zeros of this function are easily located, as being located at the points where the colors wrap completely around.

Really Discriminating. The real part of the Modular Discriminant (Dedekind eta to the 24'th), as a function of the square of the nome q=exp (i pi tau). The real part is negative in the black areas, and positive in the colored areas. Blue denotes smaller values, passing through red for the larger values.

Imagine Discriminating. The imaginary part of the Modular Discriminant (Dedekind eta to the 24'th), as a function of the square of the nome q=exp (i pi tau). The imaginary part is negative in the black areas, and positive in the colored areas. Blue denotes smaller values, passing through red for the larger values.

Jah Really. The real part of Klein's J-invariant g_2^3/delta.

Jah Really. The phase of Klein's J-invariant g_2^3/delta. As usual, black = -pi, green=0, and red=+pi.

Really Moebius Three. Amazingly, this one is studied by undergraduates enrolled in first-semester introductory number theory classes. Since books on number theory never seem to have graphics in them, I wonder if the students have any idea that this is what they're dealing with. I wonder if the professors have any idea ...

Euler's Gear. Another good name for this one might Really Totiently Toiling Away, searching for the definitive totative answer, trying to be as Dirichlet productive as possible.

Really a More Thue Investigation.

Really Random.

Next, we know that the hyperbolic conformal mappings are going to be determined by some Fuchsian group. So the question really is: given any random arithmetic series, and given any fixed equipotential line on its Maclaurin series, what is the Fuchsian group for the uniformization for that equipotential? The equipotential lines provide a continuous, differentiable parameter for the set of Fuchsian groups. The whole she-bang can inherit a metric in several different ways; and so we ask, what is the topology of the resulting set?

This all seems to be a rich area for exploration, and damned if I know of any classical treatments for this stuff. I mean, this is so basic, why didn't I get this as an undergrad, or a grad student? It seems that the pros just launch into Kac-Moody algebras and Wess-Zumino models, while I'm stuck trying to figure out what the heck an analytic function is. Even simple analytic functions, such as those obtained from the iterated tent map, seem to have an incredibly rich structure ... Sigh. Life's too short.

The Number Theory Room

by Linas Vepstas is licensed under a

Creative Commons

Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.